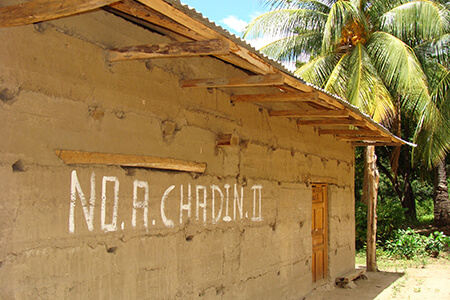

We had spent the first half of the day blasting through huge standing waves in rapid after rapid. Thrilled and exhilarated, we arrived mid-day at a broad beach on the right shore, our camp for the night. Our goal: to visit Tupén Grande, a village that would be flooded and destroyed by the construction of Chadin II dam. Besides the fantastic rapids in this section of the river, the canyon is stunning: steep-walled, and studded with both lush green trees and tree-sized cactus. Once we tied up our boats, we followed Pedro toward the village. Climbing up over a berm at the back of the beach, we picked our way across a coca and fruit farm, up another slope and onto a narrow path. The path wound downstream between fields, irrigation ditches and the occasional house for the next 10 minutes or so, when I realized that this wasn’t just a rural approach to the village; this was part of the village—it threaded its way along the river in a long narrow line. We walked between houses with large white painted letters scrawled across their walls: “No A Chadin II!” they screamed, one after another. Once the painted messages began, they appeared on nearly every building. There was no mistaking the strength of the resistance here.

Tupén Grande sits on an old hacienda, which was given back to the people after a socialist revolution in the 1990s. The old hacienda building was now occupied by families of farmers, and drying meat hung on clothes lines strung across the courtyard. The walls were falling down in places, but that seemed to be of no concern.

Twenty minutes from the boats we arrived in the village center, an earthen square surrounded by low earthen buildings, where we met the family who would host us for lunch. SierraRios had contracted with this family to make us all a meal, and they were busy with the task. Guinea pigs ran freely through the kitchen, the floor of which was a foot or so lower than outside so they couldn’t escape. Guinea pigs are common in Peruvian kitchens, both a sort of pet and a food source. A fat yellow puppy with soft floppy ears won the attention of many in the group, outcompeting its tired-looking parents for their admiration.

Behind the house we found a pile of chicken feathers that signaled the demise of our main entrée. Water trickled down a ditch, through a short length of garden hose and into a large, metal tub—the water supply for the house. Wandering back up to the square, a few of us met the head of the resistance movement, or “ronde”, who also owned the village store. He welcomed us warmly, and shared a shot of sugar cane whiskey with us. We sat with him awhile and Ben and Will translated as he spoke about the determination of the village to resist the Chadin II dam. It became clear to us that this was a place empowered. Feeding their sense of empowerment was a recent significant success. Through their determined resistance, they had won a postponement of the Chadin II project. The dam company office in Balsas, two days upstream, had closed. But we had seen the office at Balsas and looked through its windows. It was not a permanent closure. Desks and chairs and posters and maps were all still there. All it would take to start up again would be to unlock the door. It was generally considered that after the election in April, the dam company would probably be back. The villagers at Tupén Grande knew that they had won a battle, not the war. But their success had made them all the more determined to fight on.

Soon we were called to lunch. The village was quiet, perhaps because it was the heat of the day, or because the majority of the residents were off working in their fields. We sat down at a long table set up in the shaded corridor outside our host family’s kitchen, and ate boiled chicken, rice and lentils, with fresh watermelon for dessert and homemade lemonade made with boiled water. It was the standard meal we had at every village we ate in along the way—hearty if not imaginative. The dogs slunk around under the table, waiting to catch our scraps, and our friendly hosts smiled and chatted as we ate.

After our meal, several of our crew started up a soccer game with some of the young boys of the village, using a soccer ball we brought as a gift for the village school. They played gamely in the heat of the midday sun, while a donkey tied between the goal posts dodged their repeated goal attempts. The village boys beat the Americans handily, as we expected they would.

Pedro also set up a slack line tightrope between some trees for the younger kids to play on, and Ben and Ethan played with them for quite a while. Ethan tried to climb a coconut tree for our host family to cut down some coconuts, but his technique wasn’t quite right, and all he managed to get was a scraped chest and sore hands. The young son of our host family, probably 12 years old, shimmied up the tree and cut the coconuts free using a machete with expert skill, and we were treated to fresh coconut milk. We visited and rested until mid-afternoon, and then walked back to set up our camp on the beach.

Several of our group were already back at the beach when we arrived. And so were several of the villagers and their kids. Before long, some of the kids were climbing in and out of kayaks and rafts, donning helmets and lifejackets, and getting their photos taken by our group members. Kids and rafters alike had a blast.

We would return up the winding path in the evening, when the villagers were scheduled to make us a traditional meal cooked in an earthen pit-oven, called a pachamanca. We were charmed by the residents of Tupén Grande, and their pleasant, quiet life, and we looked forward to spending the evening with them, learning how to make a pachamanca.

Read more entries in our ten-part series about the Rio Marañon.

To raft and/or help protect the Rio Marañon, contact SierraRios at www.sierrarios.org